The Plant

This species is well known in Ireland, sometimes barely surviving, other times occurring in large dispersed populations as shown here in the Lough Conn/Cullin areas. These plants under good conditions will emerge and flower within a week in July and may grow tall and endure for up to 2 months if the weather is good. However, in recent years, such weather has been missing with early heavy rains leading to flooding as early as August. Fertilisation does take place and ovaries have been seen to swell but normally wither as cold wet weather becomes dominant. This area still has a healthy population though. Vegetative reproduction has been shown and individual plants persist for at least 4 years. Plants can withstand some submergence but prolonged flooding with associated wave action weakens the stems and the plants are then unlikely to progress much further even if the weather improves“A Quote from America…“

“Only occasionally are new colonies [of plants] attributed to natural long-range dispersal, for example, the arrival of an orchid, Spiranthes romanzoffianum, in the British Isles in the nineteenth century by wind-borne seed from North America.”….. and… “An even rarer orchid in Britain is Spiranthes romanzoffianum, native to wet meadows and bogs scattered widely across North America. Its dust like wind-borne seeds evidently cross the Atlantic only rarely. It appeared in a few wet meadows and bogs in Ireland in the nineteenth century and at a few others in Scotland and England since 1900” Sauer, Jonathan D. Plant Migration: the dynamics of geographic patterning in seed plant species. (ISDN 0- 520-06003-2) 1988

1.

This species is always (in Ireland) found on lake shores, though the original

(1810) record was from a seashore.

2.

It seems more regular and more abundant on west facing shores. i.e on the

east or north east sections of lakes.

3.

It often occurs at the water’s edge or even partly or totally submerged. On

lakes with great variation of long term water levels, such as L. Allen in Leitrim,

it may also appear a long way from the shore.

4.

Striking flows and curves of plant distribution have been seen in Lough Allen,

indicating a former shoreline where the seed was first deposited.

5.

We believe such seeds land on the lake surface and are then blown to the

nearest shore, in some quantities, where they get absorbed into the mud and

start their complex life cycle.

6.

It is said that seed from this species ‘may take up to 5 years to produce a

plant’. Orchids in general form a mycorrhizal association with soil fungi which

provide nutrition to the orchid to develop a large swollen root from which the

first above-ground appearance of the plant may issue as a suddenly appearing

plant which goes on rapidly to produce the typical large white spiral flower.

7.

These flowers may produce seeds in Ireland but it is at a time when late

Summer rains commonly flood their patches and drown their seed.

The arrival of Spiranthes romanzoffiana in Ireland.

We used to call it ‘our theory’ — that Spiranthes romanzoffiana populations in Ireland were derived from North America by wind dispersal — as we had become convinced of this by observing germination patterns on the shores of Lough Allen that seemed to follow shoreline contours. This is a rare orchid mainly found in the west of Ireland. It is a spectacular species and, though hard to find, easy to identify. It is quite characteristic and is found always near water and mainly, though not invariably, west facing lake shores. It is a late flowering orchid and certainly in recent years it seems rarely to set seed. Fertilisation may occur but it is rare to see this species bearing viable seed. Also, changing weather patterns have led populations of this species to be frequently inundated by Summer/Autumn rains. So where do these plants come from? Several characteristics of the species may provide the answer…Plants in Seed…

This group of 4 associated plants was established and easily recognisable in 2015 when we first came across it. It always had 4 sturdy flowering stems and they were always emerging in the same spatial framework relative to a path and to one another. They disappeared in 2020 and this is the sort of span people suggest for this orchid. Of course, they may well have existed before we came across them for the first time… So this is a vegetative group that also was actively trying to produce seed. Their location, on a raised rocky shoal, meant that they were protected from some degree of flooding. In this image (from 2017) most of the flowers were dying and a clearly enlarged ovary could be seen at the base of the flowers. This was slightly ribbed but not yet turning to brown. However, the plants survived the Summer of 2017! [A late flowering specimen from the same area showed very mature seeds on a large flowering stalk up to September 21st in 2020.] This Mayo site has consistently large stocks. Plants re- emerge for at least 3 years. But, after that, where does new stock come from? These lakes are nearer to America than Lough Allen! Does more seed bearing rain fall here? The distance is marginal in terms of the width of the Atlantic but the rainfall may be a significant factor. We have one stunning piece of evidence… The Lagoon!A Theory

As we were starting to put our observations together and form a concept (or a story) to reflect the characteristics of the species investigated here, we were aware of many traditional theories that circulate about the rare plant we are investigating and its ‘sudden appearance in Ireland’ two centuries ago! That the roots were carried by Geese… not likely as the geese mainly fly from Greenland to Ireland and the roots would in all probability be lost. That they were brought to West Cork initially by human transplantation as the family had North American connections. There is no record of this and the first specimens were found on the sea shore. That the plants were always here…Likely, but they would probably have been observed in either Scotland or Ireland — or in western Europe where they have never been found? As you can imagine it was a considerable relief when, after a deep search of online literature, Sauer’s wonderful book was discovered and bought. This is a little known source which seems to coincide perfectly with our own thinking!A particularly healthy vegetatively reproducing group of

Spiranthes — from Lough Allen… why don’t they set seed?

Lough Allen, July 30th 2016Lough Cullin complex, Mayo, a group established for many

years and surviving for at least…

A ‘vegetative’ group:

In Lough Allen — actively monitored from 2008-2016 — Spiranthes numbers have rapidly changed and most of the time any surviving plants were inundated by rising waters before any seeds could develop. Also, cool evenings seemed to stop the flowers and any seed pods from developing. So survival of the plants in Lough Allen depends on vegetative reproduction (i.e. the growth of offshoots from the root) or seed coming from America— or even the Mayo Lakes? It seems that vegetative groups can last at least 5 years (like the plants shown RIGHT) The Lough Allen population, which has been studied for many years, has been very unpredictable with numbers varying from 300 down to 1! They vary from year to year and whereas there may be a tendency to lose numbers the species has been able to re-occupy sites from which it has been missing for up to 5 years; this may have required re-seeding? Lough Allen is a recreational lake with water level controlled for navigational purposes. This has restricted the shore zone available for Spiranthes to c. 1m in height but this can mean up to 40m horizontally on flat silty shores. On such shores when a good population of this orchid is present a ‘shoreline pattern’ of emerging plants can be discerned. i.e. they follow contours reflecting, we suspect, the water level at the time seeds were washed ashore with a prevailing SW wind?Geographic Pattern of Distribution at 2 locations:

We have studied this species at 2 locations over many years, Lough Allen, Cos. Leitrim/Roscommon and Loughs Conn/Cullin in Co. Mayo. It was surprising and rewarding to see these plants at L. Allen, many years ago, as it is more easterly and in many ways seemed unsuitable for this species. Being surrounded by mountains and controlled by a sluice, water levels in L. Allen go up and down very quickly. The minimum water level is controlled to facilitate Boat Tourism in the area. They are still surviving despite this problem and some interference with their habitat. The Mayo Lakes used to be separated by a cascade but the relevant blockage was removed in 1965 and now the two lakes flow together seamlessly, though there are separate water gauges for both lakes! L. Conn is a big lake with S. romanzoffiana occurring at almost every quarter in many of the suitable habitats available to the plant. Two interesting patterns are emerging, one a slightly curved western shore with identical habitat over 0.5km. Many plants were seen here in 2016 at a fixed distances from the water and copying the shores gentle curves. (i.e. water deposition?) Secondly, at the north end of the lake a small lagoon exists which has a very narrow/dry entrance in fine weather. However, high water floods cover a large circular area behind this entrance in Winter. And, of course, the typical swirl pattern of new Spiranthes plants matches the (presumed) level of water at time of seeding! Water levels rise (and drop) slower than L. Allen. It seems plausible that the distribution of c. 100 specimens at Lough Cullin in a broad bay facing south west and all at very close to the same height requires water based seed deposition. The plant is tolerant to a range of conditions and elsewhere grows happily further away from the present water level. Most specimens recorded at Lough Cullin seem to be at roughly the same ‘altitude’, with the exception of a stony bank that has plants 20cm higher than most of the flat shore. This is hard to judge, and there is small local variation, but when the Autumn floods start many of these specimens survived whereas other specimens were submerged in 10 - 20cms. of water on one particular day.What’s going on…

The pictures above are of some of the finest displays of Irish Lady’s Tresses in the area. Fertilising insects are infrequent on Spiranthes mainly due to cool exposed habitats deterring Bees. Flooding of the plants in flower and available for fertilisation, on the other hand is common. This species does not seem well adapted to our climate? It is part of the Irish flora but is also, we believe, a wind blown vagrant perpetually migrating across the Atlantic only occasionally able to settle down here and in Scotland but rarely elsewhere. How long does it take to acquire resident status?The Lagoon:

In these circumstances can they provide seed to populate the next generation of plants? This study area, which we call ‘The Lagoon’ (an aerial Image and an Indication of stock is shown (RIGHT)). It had a total of 135 flowering specimens in 2016. This is a ‘wet’ lagoon. i.e. most of the area has flowing water. It is essentially flat land only joined to the lake at very high water levels. On either side of this lagoon are older locations where the lake in the past forced an entry during earlier winter storms? These lagoons dry over some years and trees start to grow. We believe that in the short period while this lagoon has been open seeds have been carried in through the narrow entrance to the lake. These flow into all the channels and ponds (all at the same level) in the lagoon and settle where they land. Plants then grow along those settled channels, forming an association with mycorrhizal fungi and only emerging several years later to flower. Our evidence for this is the pattern of distribution at the same height above water and following the course of present or previous drains! This implies that lakes in the west of Ireland at certain times carry a lot of Spiranthes seeds floating on their surfaces? This is, nonetheless, more plausible than seeds casually landing on ideal terrain! Where do these seeds come from…The Seed Source…

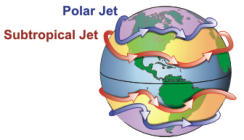

Might we suggest… America? S. romanzoffiana does not occur in continental Europe or Asia and apart from Ireland is only found in Scotland (and, recently, Wales). We don’t see how there can be a sufficient stock of plants here in Ireland — they were never common — to provide abundant seed? From the West of Mayo the next stop is North America, where this species is widespread as Sauer* points out. They occur in all the eastern States and in Canada. The nearest population to Ireland would be in Newfoundland and Labrador, just where the Jet Stream often passes. The Jet Stream is a strong upper-atmosphere wind now thought to affect our climate very dramatically. If it moves south we get rain, if it moves north we get warm weather. If you look at maps of the Jet Stream it will frequently be seen to travel from North American coasts directly to Ireland and Scotland. Scotland seems to be getting a good stock of these plants in recent years; has the Jet Stream been moving north? There are mechanisms whereby light seeds can be lifted into the upper atmosphere and if the upper wind is strong they could be in Ireland in a day and brought to ground in the Summer rains often associated with the Jet Stream? * at the start of this Report.A special Habitat…

The site image (Below) shows The Lagoon habitat for this species within the Conn/Cullin complex. It is a micro-site of about 2.7 hectares with complex erosion and settlement processes at play. These processes clearly provide an ideal nursery — we have never seen so many Spiranthes in such a small area. It is exciting and does bode well for one of Europe’s rarest species. It is an adaptable species — a curious plant — and as long as some shorelines are left natural it can cope and survive….

Jet

streams

are

fast

flowing,

relatively

narrow,

air

currents

found

in

the

atmosphere

around

10

kilometers

(a

very

common

altitude

for

airplanes)

above

sea

level.

They

are

a

purely

natural

physical

phenomenon

forming

where

masses

of

air

at

different

temperatures

meet.

Hence

the

connection

between

global

warming

and

a

greater

awareness of Jet-streams and their impact on our weather.

NetWeather.tv

provide

beautiful

animated

maps

of

the

Jet

Stream

for

up

to

14

days.

Archival

data

is

harder

to

find,

i.e.

what

way

was

the

Jet

Stream

5

years

ago

between

Labrador

and

Ireland?

But

current

images

show

common

wind-speeds

in

excess

of

200

km/hr. How long does that take to cross the Atlantic? (HINT: 19 hrs)

Records:

All specimens were GPS’ed. This data can be superimposed on Open Source mapping and does reflect the observations recorded here. However the records are much too cluttered to reproduce individually. We have found that using a GPS is also a very convenient way to quickly count large numbers of randomly dispersed plants. We use it as a routine nowadays. Also, with care and time, accuracies of close to 2 meters can be obtained — which is truly amazing! The remaining two images show the variety of habitat from bare to lush vegetation and the variety of specimens we encountered from stunted to splendid, though none as splendid as the group at the top from a mature colony

Our evidence has been strengthened and, as of Autumn 2017, we feel we have

proof of Spiranthes Migration across the Atlantic… For an update on our

S. romanzoffiana research please read our 2017 Report on this topic Below.

SpiranthesMigration

The Lagoon: evidence of water deposition…

NE corner of L. Conn. This Map shows settlement pattern. Each symbol represents many

specimens and indicates their occurrence on sandy banks at the edge of channels.

Conditions in 2016

The two images show the condition of the Site in the Summer of 2016. The plants were flourishing; this is when we recorded the maximum number of 135. Numbers have declined since then mainly due to ever increasing flooding at critical times. Both these images are from 2016 and both show the predilection of the plant for sturdy tussocks adjoining one of the many almost flat drainage channels — a small stream enters the area at the north of the site. This was quite a unique habitat and a fascinating place to explore and understand. At the time the photograph was taken there was a very slight slope to the main lake, as can be seen by the gently flowing water. However, it seems unlikely that this site was at risk of drying out in the near future. Indeed it would have become submersed in the rains that followed.

Succession:

At the time of first discovering this site it was a peaceful beautiful place with Nature adapting to a changing environment. The records and reporting, shown here, date from2016. For technical reasons this Page has had to be updated and we have taken the opportunity to bring our information, also, up to date. The Lagoon still survives with numbers staying constant or reducing. 2020 was a poor year here as early specimens arising in July were soon rained on, flattened and stunted. These two images date from 2016…

LEFT:

The Main Channel in 2016

Weather conditions were favourable as

can be seen from the lush grass

developing along this channel of slow

flowing water.

We have not been able to measure the

drop from the back of the lagoon to its

exit to the lake, but it must be very small

as these channels flow slowly or may

even dry up if the feed stream

disappears. Certainly for many weeks of

good weather there will be no ingress of

water from the lake; that is a feature for

later in the year and is the essence of

the mechanism whereby this unpre-

possessing parcel of land became a

haven for one of Ireland’s rarest plants.

RIGHT:

Settlement of the Lagoon.

The ‘settlement pattern’ is quickly followed by a ‘succession pattern’

whereby plants and wildlife attracted to the area start to take over!

We do not know how old this lagoon is but it is an active lagoon.

200m to the west is a similar lagoon that has now been cut off from

the lake and seems inured from flooding by a barrage of Alder trees

on a high sand or gravel bank. Alder trees are rapid colonisers of

unstable land with the propensity for adding Nitrogen to the

otherwise mineral soil and binding the substrate together with their

sturdy roots.

This mature plant was recorded in 2016 but it was deeply enclosed by

Bog Myrtle, high grasses and scrub. The pair of Orchids seen are not

in an ideal situation and will probably by now have been overgrown.

S. romanzoffiana appreciates shelter from trees like Alder but

otherwise tends to flower in open ground or ground that was open

before Rushes, Phragmites and large terrestrial shrubs take over and

exclude the ephemeral Spiranthes!

Spiranthes romanzoffiana: 2016 study

This is an edit and substantive re-working of survey work for this

species mainly in the Lough Conn/Cullin complex in north Mayo. The

original report was almost lost but we have recovered the

photographs and edited some of the original text. However, this is

substantially our observations from 2016… (November 2020)

9th August 2017

Iconic image

courtesy of

Wikimedia

Commons