Click on Images

where you see this

symbol.

Strandhill Promontory.

Between west Sligo and north Sligo coasts there is an impressive free-standing Mountain, Knocknarea. West of this is a beak like promontory controlling the seas access to one of several tidal inlets around Sligo. This small area (shown in the map below) has a diverse range of habitats and wildlife. It is also an important amenity/recreation area for people of the area with impressive ocean and mountain vistas. An SAC, it contains many plants typical of a sandy habitat containing different niches within it varying from shoreline to high dunes. It is one of several favourite places along the Sligo coast. Others would include Dunmoran Strand and Mullaghmore which makes this Sligo coast rewarding to naturalists throughout a long season, May to October. Of course, at other times other interests take over with populations of Seals and Geese dominating. We have focussed in this page largely on the rare and unusual flowers of the area, Gentians, Orchids, and salt tolerant species. But its shoreline, at any time and at all stages of the tide, can be rewarding for wildlife with many wintering birds and large numbers of Seals gathering to reproduce. Konocknarea, shown BELOW. is the sole upland area and arises in solitary splendour unattached to any chain and dominating the landscape with dramatic cliffs, cairns and a Burial Site. West of that is the ‘beak’ of Strandhill Special Area of Conservation with an Atlantic beach to the west and a large sheltered sand and mudland behind for seals and visiting birds.

Strandhill Habitat

Beach, bay, sand-dunes, machair, estuary, tides, sandbanks… this small area of Co. Sligo has it all.

WildWest records and celebrates Nature, Habitat, Scenery on the western seaboard of Europe bringing you reports on how our wild communities (plants, animals,

insects etc) are surviving in Ireland and other western extremes.

24 October 2019

Published

1400px

site. Designed for Desktop or Laptop…

The Coastal areas…

The area studied is the large squarish bay and the dunes and calcareous grasslands on its north and west sides. A convenient car park can be found on the north-east corner of this bay and all the important botanical sites are within easy walking distance. A you enter Strandhill natural habitat you are struck by the variety of ‘places’ within one small area. The beach to the west can be cool and windy but inside the shallow bordering dunes it can be warm and protected leading to an explosion in orchids over a long Spring/Summer season. Very high dunes occur at the north of the photo (ABOVE) and are largely used for recreational purposes. Stable for a number of years, but not vegetated, they consist of a large area of moving sand (and people) with little undisturbed vegetation apart from the critical marram grass at the dune tops.. Another shore is the exposed Atlantic coast on the north side of the huge sand pit that forms this unique ecosystem that can be explored in a day… or over many years. People walk through this for all sorts of reasons… to get from the car-park to the beach, to have a picnic, to slide down the dramatic dunes between the western wilderness and the golf club and town to the east. Many of these photographs were taken on one day. The dramatic waves and ‘storm’ were not as massive as they look and the effect was created by using a big zoom and a fast speed to focus on the waves and blur the lighthouse which is in fact some distance away. The large estuarine area between Strandhill and the dominating mountain and cairn of Knocknarea is beloved of seals, Brent Geese, wading birds, diving ducks, Auks and Great Northern Divers fishing in the deep channels during the Winter period. It is a vast area with regular large ebb and flow of fresh seawater leading to ripples, tidal rips, deep channels and smooth silt pans where the Common Seals like to pull out and sing (or lament) before giving birth. Vegetation of zostera and ulva seems suitable for certain ducks but there is not a large population of grazing ducks though Teal, Wigeon and Mallard are dispersed in small groups all over the vast area of mud that is Ballysadare Bay. Mergansers and Long-tailed Ducks are present in small numbers during Winter around the outer margins of this estuarine and coastal system. A final specialised niche can be the zone of halophytes at the foot of dunes and just above the high tide. These are resourceful plants and help stabilise sand dunes and sandbanks. It seems strange to see them flowering in a ‘desert’ right through into the Autumn. But the tolerance for salt also provides them with a tolerance to drying out in the form of waxy skin and active stomata. [The numbers in the Map refer to the five sub-habitats we have defined and described below.]

1. Marginal Sandy slopes…

After crossing the mudflats and passing the Golf Club there is a small gap in a fence leading over low sand dunes and into an area of many small sandy hills and valleys with a great variety of tracks and hill slopes to explore. Often this area is sheltered from the wind and it can be warm. The whole area is composed of low hillocks and banks of sand and calcareous deposits formed from generations of sea shells washing up to form these hillocks. It is these shells that provide the calcium that so many orchids and other plants enjoy. These marginal slopes, particularly close to the south of the promontory, are abundant with orchids. Most — but not all — orchids like an alkaline substrate! Walking up the path from the bay, the large dunes appear ahead — spectacular but not flower rich! It is the lower banks that are covered with a rich tapestry of flowers from May to October. There are a variety of common (pinkish) orchids, red pyramidal orchids and other rarer orchids with very special needs. Typical sand dune plants like violets and roses and clovers abound along with the grasses and sedges we struggle to identify. However, this area is almost entirely bare of any trees. This, and the hot sun that can be experienced here, lead us to think in American terms of prairies and large open landscapes…

ABOVE: The impressive Knocknarea mountain stands on

its own to the north of the habitat. Ballysadare bay seems

healthy with good growth of green seaweeds. However it

does not attract very large numbers of ducks or geese; the

south and inner parts of the bay being more popular.

Brent Geese feed among rocks in the sea channel.

BELOW: Some of the many Autumn/Winter visiting

waders found busy on the shoreline as the tide recedes.

These are Ringed Plovers and Sanderling (INSET) The bay

is more useful at high tide in Winter with the many fish

eating birds congregating in the fast flowing channels as

the waters ebb and flow.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

2. Dune bottoms and flood areas…

Within a short distance from the ridge of surrounding sand hills (small to the south, larger to the north) there is an area of more settled and greener grassier habitat. This can be either flat or hilly. The hills may be small (3m.) but can still be noticeably drier and plants will easily wilt there. Most of the species considered here, and there are a couple of rarities, are very moisture dependent either by way of flash flooding or low lying slow-to-drain areas. It is a fascinating area with several specialists here in good numbers each requiring and finding the ideal niche for them to seed, grow and flower.

BELOW: Large and Small dunes.

Approaching from the southern entrance to the site via the rippled sands of

Culleenamore Strand, the high dunes appear as a backdrop to the lower

marginal slopes that hold most of the rare and common dune flowering plants.

Typical species associated with these

conditions would include:

1.

Pyramidal Orchid

2.

Common Spotted Orchid

3.

Bee Orchid

4.

Burnet Moths

5.

Wild Thyme

6.

Lady’s Bedstraw

The image (RIGHT) shows the typical Burnet

Moth of Strandhill. This pair is mating on

one of its favourite perches — the Pyramidal

Orchid.

The Pyramidal Orchid (Anacamptis

pyramidalis) is a widespread species

dominant in this habitat and a uniform

densely flowered plant. It is abundant on

these slopes, occurring in peripheral low

level dunes at the edge of the study area as

well as on hillocks and sandy banks within

the area. It grows rapidly but will wilt quickly

in hot weather as seen in in the image of the

full plant, BELOW.

RIGHT:

Bee Orchid Ophrys apifera

Also widespread in more or

less the same niche as the

Pyramidal Orchid. It seems to

be all about water — but NOT

too much of it — warm

weather, and nutrition. The

Bee Orchid is quick to flower

and very quick to wither.

They are a successful species

due to adaptations in their

reproductive systems

(Discussed elsewhere). A

closely related species (the

Fly Orchid) does not occur

here as it is very limited in the

way it is fertilised.

This specimen (it can be

enlarged) shows the

rostellum, viscidia and the

released pollinia now

dangling in front of the ovary.

Both self fertilisation and

fertilisation by visiting insects

is thus possible making for a

successful species!

BELOW: A typical steep but not high bank rising up from one of the many paths and water channels. It provides the warm

southern facing aspect that helps orchids to grow and a degree of shelter from drought and wind. Apart from the numerous

Pyramidal Orchids, Hawkweed is abundant along with Lady’s Bedstraw — a grouping of species typical to Strandhill.

ABOVE: An uncommon Common Orchid — this is a spectacular and beautiful cluster of the Common Spotted Orchid

(Dactylorhiza fuchsii). It is very rewarding to come across these common species when a fresh healthy vigourous specimen or

group is found. All Irish orchids will produce these ‘perfect models’ but they need perfect conditions and they don’t last long!

RIGHT:

These plants will thrive in differing areas but a habitat can be defined by the plant associations that are particularly

notable in defined sets of circumstances. The Carline Thistle (Carlina vulgaris) and Wild Thyme (Thymus polytrichus)

are also widely present on exposed sand hills and in the next section dealing with flatter long-grass conditions.

These specialists can be cited

as:

1.

Marsh Helleborine (RIGHT

2.

Marsh Orchid (Far RIGHT)

3.

Frog Orchid

4.

Field Gentian

5.

Violet

All these species seem to

occur in low ground either wet

or damp or where water

regularly flows or stays in

pools for long enough to

support the species. Several of

the species display ‘Spiranthes

alignment’, a phenomenon

where plants align along a

previous water boundary at

some time in the past, either

recent or long ago!

The Marsh Helleborine

(RIGHT) is common in marshy

areas of most sandunes (viz.

Bull Island, Co. Dublin). The

density of specimens is greater

when the wet area is larger.

This group is probably the

biggest colony at Strandhill.

Above RIGHT

Marsh Orchid

Dactylorhiza coccinea

This also loves wet zones

but can occur on the

slopes of nearby drier hills.

Dog Violets

Viola riviniana

A common Violet but a

dominant species at

Strandhill. It loves dune

bottoms and nearby slopes

but not in areas of semi-

permanent water.

It is of interest as it forms

dense ‘bushes’ or colonies

set apart from one

another. Is this a response

to floods and droughts,

lack of trees, or is it down

to the alkaline substrate?

This species flowers over a

long period from April to

October and always occurs

in open areas such as

wood margins, shores and

calcareous grasslands.

It is curious the way that, at

this habitat, it is mainly

present as large separate

clumps. These clumps are

universally lush and green

with healthy large leaves —

even when the orchids and

gentians are wilting!

Perhaps these clumps are

one plant with deep roots

that can withstand

occasional severe

downpours.

Trees and Wildlife.

All of the area is naturally almost devoid of trees. North of the area some native Scots Pine survive with associated Pyrola. In this Study Area there are only two trees! This limits the scope for breeding birds and the common species occurring would be the Meadow Pipit, Skylark (ground nesters) and the Stonechat. LEFT Alder This stunted Alder seemed to mark the site of a spring or a drain (or both) with visible gullies and boulders under the bush. It also marks the lowest part of the Dune bottoms so, presumably, all rain water flows into these lowlands and eventually runs out through subterranean connections under this bush. LEFT Stonechat. This tree is the highest point in this birds territory. They breed here and spend most of their day flitting from perches in the Marram Grass and this clump of Alder. It seems that the pair breeding here would be the sole territory holders in Zone 2 but there are probably other similarly isolated pairs further south.

ABOVE: Prostrate Juniper.. Juniperus communis ssp nana ?

We have walked this area religiously and have never seen

another specimen of this species… Prostrate Juniper (but

possibly a variant of the normal Juniper). It is frequent in

exposed western seashores and cliffs such as Dernish Island in

north Sligo not far from this location, also in North Mayo high

cliffs at Portacloy. It is a tree but rarely grows taller than the

specimen shown. Many expansive specimens occur on the

abandoned Dernish Island and perhaps seed has been carried

from there. It does seem somewhat out of place on this sandy

but alkaline flat. This area of Sligo is based on Glencar

limestone but the other two locations are on psammitic rocks of

metamorphic sandstones.. acid rocks?

However, judging by the wealth of base loving plants present

here it is clear that the underlying Limestone Formation and the

surface deposit of sand laced with calcareous shells is providing

the suitable alkaline and mineral conditions required by the

orchids and other lime loving plants.

Colour…

Colour is less vivid in Autumn and these September/October discoveries were delightful to see as the flowering season was ending. The Frog Orchids are familiar occurring as they do in Kesh Mountain, Co. Sligo fairly close to where we live. But they are an interesting orchid that often may never reach a mature state due to grazing or exposure to harsh weather. The specimens from Strandhill were hard to spot when first observed as their bright green leaves and bud blended well with the damp background they were in, but they quickly developed into more discernible and sturdy specimens. Milkwort… The pictures (LEFT) are of Common Milkwort (Polygala vulgaris) a low growing herb found in grasslands and common at this site. The colour and size of these very small plants varies as shown. These pinkish and blue- ish variants occurred side by side and colour variation was visible to the naked eye. Sun intensity was varying rapidly at the time. b) Field Gentian (BELOW), Recording the Frog Orchids led to a later discovery of Field Gentians in the same area. These were in among similarly coloured commoner plants. Tonally, they seemed in between the Milkworts but all the Gentians were of a pale purple hue very much in harmony with their commoner companions. All these images were taken under bright Autumn sunshine and many different Gentian plants were photographed. It seems that the Gentian flowers were all of the same colour but the Milkwort plants genuinely occurred in slightly darker shades of red/blue which also corresponds with a mental memory of many of the Milkworts looking slightly different!Two unique and unexpected plants.

We have been investigating this Strandhill Habitat for a number of years and were familiar with the main plant populations and the way weather conditions encouraged or discouraged large scale flowering in each species. The Bee Orchid this year, for example, was well represented but only over a short period as many of the plants growing high up banks and exposed to the sun simply dried up within days. a) Frog Orchid Dactylorhiza viridis At the end of June we were looking for other interesting species. A few very tiny emerging plants of this species were found in one cluster in the slightly humped water pathway leading into the sump at the Alder bush. This small clump over the next few weeks developed into a record of 40 specimens in the same general area. Some of these plants were the finest example of the species we have come across. The Frog Orchid occurs in many different sites in Ireland either on Limestone (Kesh Mountain, Co. Sligo) or on calcareous grasslands or dunes (Sheskinmore Nature Reserve, Co. Donegal). We know of no previous records for this species here? The niche we have found these in is on lush dune bottoms rather than on the sloping borders of bare dried up flood channels where Field Gentians were later seen.

Field Gentian

Gentianella campestris

After the excitement of seeing a

new successful occurrence of the

Frog Orchid it was good, a few

months later, to discover a new

unfamiliar species of Gentian

emerging above the wet fringes

of the same habitat.

Instantly different from the bright

blue Spring Gentian of the

Burren it seemed smaller than

the Autumn Gentian. Final

identification was based on the

corolla — the petals and sepals.

These specimens were very small

when first encountered growing

on lower slopes of small dunes,

which in mid October were

closely cropped. The opening

flowers lend 50% to the height of

the plant but the flowers

themselves rarely fully opened

this late in the season.

As these photographs show this

plant had 4-petal flowers and the

Calyx had Sepals of unequal size

with a large one either side

overlapping the narrower sepals

in between. Both features

identify these plants as Field

Gentians.

This is a new species to us and no

record of it occurring in the

Strandhill dunes has been found

yet. October is a time of year

when botanists tend to switch off

and we would not have come

across these Field Gentians had

we not made such a close study

of the habitat earlier in the

season and returned to check it

out regularly!

3. Settled Sand Dunes…

At the south-western flank of the Flood Area described above there is a medium height linear sand dune which marks a change of habitat. The flood area has been subject to recent flooding, tidal and wind damage. West of this the dunes are stable and more or less undisturbed over a long period. This reduces the species richness.

Leaving the Dune Bottom

and heading north and

west, this small valley

(LEFT) brings you into an

area with almost

complete grass cover

including large areas of

waist high Marram.

This is a good valley for

invertebrates and the

bank on the right

particularly attracts

butterflies and dragonflies

as shown on LEFT

Vegetatively the change of

habitat is reflected in the

Harebell showing up

prominently in the

foreground of this picture.

A common species which

likes more sheltered areas

from mountains, to rock

shores, to sand dunes.

Slopes are a common

niche as this plant does

not like flooded or

permanent damp areas.

BELOW

These cases are to be seen over much of Strandhill, wherever these 6-spotted Burnet

Moths (Zygaena filipendula) occur. The yellow cocoon has a black pupal case from which

the adult moth has emerged.

RIGHT

Harebell, Campanula

rotundifolia

Close-up of some of the

Harebells from this warm

sheltered valley. Many

plants have colour variants

but white Harebells are not

so frequent. They are

graceful abundant flowers

with a long flowering

period — somewhat under

appreciated jewels of

mountains and dunes.

BELOW

A largely flat area, like a

prairie, between the two

marginal lines of dunes,

this zone is overgrown with

marram grass and not

botanically rich. But it is a

good area for snails and

insects and the Pipits and

Larks which feed on them.

List of Habitats/Zones

1. Low Dunes

2. Dune Bottoms and Flood areas

3. Settled sand dunes/prairie

4. Halophytes and Deep dunes

5. Beach/shore defence

Aerial Image:ExpertGPS/MapBox/OpenStreetMap. Added Notes: Wildwest.ie

4. Halophytes and Deep dunes…

There is an area at the southern tip of this dune system that is interesting, dramatic and little visited. Just offshore one of the main channels allowing the tides in and out passes close to the beach. Consequently the shore is steep and fast water will run past at peak tidal flow (about half way between high and low water) — making this a popular hunting area for seals and birds. On the inland side of the shore there are steep defences in terms of continuous dunes on the margin of the shore and a pocket of a few very small steep sided sand baby dunes. These are a haven for a variety of specialist plants like Harebells and Roses as the area can be very warm dry and sheltered. Mating snails love this area!

ABOVE: Sherrard’s Downy Rose, Rosa sherrardii

These Autumn pictures are of a cluster of these Roses found

in a very limited area in these deep dunes (Habitat #4) We

identify it based on the leaf shape with slight point, toothed

edges with glands on the underside and on the stems and

hips. Up to about 2m. tall with slightly curved sharp thorns.

The red moss like growths on the stems are called Robin’s

Pincushion and are a gall that distorts an axillary leaf or a

terminal bud. The gall is produced by Gall Wasps, Diplolepsis

rosae.

Two episodes of Frog Orchid

emergence occurred due to

weather conditions.

Galling Roses:

Roses can be hard to identify especially when out of flower. Two types are shown here

bearing galls resulting from brood parasitism by various species of Gall Wasps..

BELOW: Burnet Rose with gall from Diplolepis spinosissimae wasp.

This is a prostrate rose creeping along bare or lightly covered sand dunes. (It is from Habitat

# 3 above — Settled Sand Dunes). The gall is formed in a similar manner to that of the

Downy Rose (RIGHT). An egg from the wasp is laid in a leaf or bud axil. The developing larva

releases chemicals which trigger an unusual growth from the parent plant. In the case of the

Burnet Rose the growth forms a polished spherical cradle cupped in the leaf from which it is

fed. Other common examples of galls are Oak Apples and Witches Brooms found on Birch

trees.

Halophytes:

Halophytes are salt-tolerant land plants often

associated with arid climates but important in

Ireland on seashores where these plants are

resistant to salt spray, submergence in salt water,

or tides on a regular basis. The European

Searocket Cakile maritima (LEFT) is a typical

example found around the sandy back shore of

Strandhill promontory. This plant can survive in

areas most exposed to both wind and tide.

This, and the Frosted Orache Atriplex laciniata

(RIGHT), help extend the sand dunes at the tip of

this site by forming series of clumps along a

current margin leading to a build up of sand along

the upper tide mark.

Perennial Sowthistle Sonchus arvensis

A secondary coloniser, it is normally associated with other plants on disturbed

ground or newly forming vegetation. It is the perennial ‘version’ of the Dandelion. This

photograph shows the Sowthistle with Harebells and Lady’s Bedstraw.

Sea Sandwort Honckenya peploides

Another succulent low growing plant with a large root system, grows at the base of

dune systems especially, in this case, in the calmer inner south facing part of

Ballysadare bay. The glossy leaves help it retain water

Dune Erosion and Settlement.

Here an exposed section near the mouth of the bay has been

eroded by wind and water but still shows tufts of marram,

Orache, Sowthistle and Searocket on the exposed flat sand.

Finally we have reached the end of the Spit facing the open ocean and controlling, through narrow channels, the ebb and flow of the tides. As the water leaves

the large area of bay behind the dunes it passes through 2 major drainage channels with very fast tidal flows particularly when the tide is going out. Further

banks occur across the mouth of the bay and these are dry at low water —the breaking waves indicate their position.

In the distance Raghley can be seen, looking like an island, but it is joined to Ballyconnell with the low hills rising on the right towards Lissadell. It is impressive

that, even over such a short distance (8.25 km), the low lying land between Raghly plateau and the Lissadell hills has disappeared. It seems after all, that the

Earth is curved! It took us quite a while to work that our but our dog, Beau, seems to be ahead of us in his search for Australia!

5. Beach & Shore defence…

Coastal Erosion at Strandhill.

If you look at the aerial photograph at the top of this page it would seem that this Strandhill promontory, composed of nothing but sand, is very exposed to the Atlantic. Yet it has not suffered major damage over many years. Other dune systems, and coastal areas, around Ireland have been devastated by apparently rising sea levels and undoubted increase in storms in the Summer/Autumn seasons. We have known this habitat as a place for regular walks with one dog or another over 15 years and the broad overall landscape has not changed materially. Why is this?Factors protecting this habitat.

As you can see (photo ABOVE RIGHT) the sand on the most exposed part of the shore is deep and fine with no shore defences installed apart from the naturally occurring boulders in the background. Nearer the town itself the big dunes and wash-out was caused by a spectacular breach in the traditional shore defences about 10 years ago. To prevent further damage this area and the shore in front of the town and further north has been extensively protected by rock armour to protect the town and its thriving Surfing Industry — another testament to the size of the waves to be found here! The main photograph (ABOVE) taken looking North does provide some further clues to the limited damage exposure is causing at this point. Despite appearances there is land joining the two higher areas of ground shown, Raghly to the left and Lissadell to the right. This barrier is only 8km away so there is only a short stretch for waves to build up and no means whereby ocean waves can directly approach the beach from the north. Furthermore, this photograph is taken at mid to low tide and the offshore breaking waves indicate bank after bank of sand taming the waves before they ever reach the sand-dunes — apart from very high tide levels! However between Raghly Point and Carrodough Spit (# 5 on Aerial Photo) there is a clear uninterrupted line of site to the NW. The Spit is protected from westerly wind and waves by Sligo’s north coast which stretches further north than Strandhill. Also, along the exposed north westerly line there is a shoal called Turbot Bank which straddles the Sligo Bay entrance and is largely composed of sand. So here is to be found a large reserve of sand that can wash up and rebuild the Strandhill shore and dunes. This may explain how a geographically exposed site in North West Ireland is not suffering the level of erosion and territory loss one might expect.Stabilising the substrate and protection of rare species.

Substrate is the base in which plants are anchored. It can be sand, rock, soil, etc. These various media erode at different rates, sand being the most mobile where it is not anchored by plant or other material. Unfortunately most of the Strandhill peninsula is largely sand, with shell fragments, on top of underlying limestone bedrock. Great pH for plants but a hard environment for the vast majority of plants to settle in. None of the exotic orchids would be present in Strandhill without the marram and other ‘humbler’ plants to do their basic task of stabilising the landscape.History of Erosion at Strandhill.

Mapping of dune movements is hard to find. More information on this and the habitats can be found in the following links. Item 3 in References below records the status of dunes c. 2010 showing a breach in the high dunes south of Strandhill town. Otherwise there is little record of change. References: 1. NPWS Site Synopsis 000626 Ballysadare Bay 2. NPWS Salt Marsh Survey. Detailed project on all Irish salt marshes including parts of Ballysdare Bay/Strandhill 3. Ballysadare Bay SAC Conservation Objectives, NPWS. Contains Maps of Dune systems from 2010-12

A nice mauve version of that important stabilising plant, the Searocket, serves to

conclude our musings on movement of climates, and beaches and habitats.

Meadow Pipit

Anthus pratensis

BELOW Soldier

Beetle

Rhagonycha fulva

feeding on

Hogweed

30 June2019

13 July 2019

13 July 2019

Common Centaury:

A common but pretty

plant of dry areas.

16 October 2019

20 October 2019

LEFT: Common Blue Buttterfly Polyommatus icarus

Common Darter Dragonfly Sympetrum striolatum on

Mouse-ear Hawkeeed

SUPPLEMENT: 2020: Another Summer, another Autumn…

It’s not the joy of creating a new page but the easy comfort of returning to work well done and adding to it with one more years experience and the wonderful changes that years and seasons bring about.. Strandhill in Co. Sligo is known for it’s botany but not renowned for it. It is a famous beach and surfing paradise but, for people like us what lurks between the sea and the back strand is equally magical — no more so than this year. In September many surprises lurk in among the well trodden ways through the mighty sand dunes. This month having just finished the annual Spiranthes rommanzoffiana count we thought of that other species, S. spiralis, and went to explore one of its many haunts, Cross Lough and the western dunes of The Mullet in Co. Mayo. And we were rewarded with 100’s and then 1,000’s scattered over the lake shore and low sand dunes. But this is not about Mayo; we want to add to our knowledge of Strandhill, it’s natural history, and the pictures and species that make this place perfect for all naturalists or amateur botanists.All this delight, devotion and desire!

We'll fling ourselves into September's riot!

Immure yourself within the autumn's rustle

Entirely: go crazy, or be quiet!

How when you fall into my gentle arms

Enrobed in that silk-tasselled dressing gown

You shake the dress you wear away from you

As only coppices shake their leaves down!

(Autumn. Boris Pasternak)2020: Autumn’s rare flowers at Strandhill

This Autumn we seem to have finished early with surveying S. romanzoffiana and it is time to study its cousin S. spiralis and 2 other spectacular and unusual plants. LEFT: Autumns Ladies Tresses. Spiranthes spiralis On our first return, from botany further west, this was the pleasant surprise that awaited us in the quiet places where few people wander and where there is no grazing and few dogs — a pristine site that enables little miracles to emerge and prosper. Obviously this is a close relative of S. romanzoffiana but it is a plant with a completely different nature but equally charming characteristics. It shares its fondness for our western coasts though it occurs much more widely. In a small spot in Mayo we counted 24 in a 50cm x 50 cm square and everywhere else within view they also appeared numerous. There must have been 1,000’s. We didn’t attempt to count them! They share a fondness for our western seaboard but will grow on dry hills not immediately adjacent to water. In Strandhill this year they are also abundant and occurred over a large central lowland location as indicated in the aerial view BELOW. Look in the short grass nearby and you will find them in good numbers. A bit earlier in 2019, in very dry conditions, The Frog Orchids and Field Gentians were there but no Autumns Lady’s Tresses? RIGHT Frog Orchid. Dactylorhiza viridis In Strandhill these orchids flower much later than they are meant to. End of August is their season and, indeed, many well wilted specimens complied with this rule; just certain specimens seem to get a boost and emerge late and flower late. This young plant starting to flower was taken on 6th September. Similar flowering of large groups took place last year as can be seen from the top of this page.Field Gentian Gentianella campestris

We saw these last year, but scarce, struggling and very tiny. This year they were springing up all over the site but most abundant in wet hollows and narrow drainways leading through the central low calcareous sand dunes.Spiranthes spiralis

Details and Life History, as we know it! The 4 surrounding photographs show samples from Strandhill in early September, 2020. The dune areas of North Mayo and North Sligo are good locations for this species. Differences from Spiranthes romanzoffiana: • Spiralis is smaller but with similar spiral flowers which can be few to over 20 florets. • The rotation is sometimes stepped or can be smooth like a spiral ladder. • Leaves are narrow and seem greyish like the stems, due to a thick covering of fine hairs. • Not found close to water (or in water) but do have preferred wind-lines halfway up an established dune where they occur in patterns removed from any water. Also, will form shapes and curves around lowland depressions. • Are clearly not dependent on water for dispersal and pattern of occurrence may suggest wind deposition? • Like its big cousin it reproduces well vegetatively with family groups of 3 or 4 common. These may be several years old and typical of slopes. • A ring of leaves called a ‘rosette’ develops in the Autumn after the flowers are finished. • Plants may live for up to 10 years but the extent of their flowering over the years may weaken the specimen.

Seed Production in Spiranthes group:

There are only 2 species of this genus in Ireland, the Irish Lady’s Tresses and the Autumn Tresses. They neatly

share the flowering duties with S. romansoffiana flowering from July to early September (but very dependent on

conditions) and S. spiralis from July to September. In Ireland the end of the season for S. romanzoffiana is the

start of the flooding of its lakeshore habitats which is now earlier than in previous decades. Flowering,

fertilisation and seed production is unpredictable. The survival of this species is largely dependent on vegetative

reproduction (later buds) or seed from America!

In Spiranthes spiralis (a plant we are rapidly coming to appreciate) there is no similar risk to survival and plants

can appear in their thousands in suitable conditions. In the panel below we have collected samples of mature

flowers, mature plants with seed capsules developing for released. Seed in both species is similar and very light

and clearly designed to be taken away by the wind be it on a prarie (America) or maritime dunes or inland short

grasses (Ireland).

A shy Spiralis…

This single plant seemed to be demurely hiding

behind a veil of flowering rush — indicative of a

plant growing in moist conditions. A mature

plant with 20 florets, some dying and some

opening. The size of the plants seems to reflect

their age. In an ideal habitat it is unfortunate

that to sit on the ground may mean squashing

many tiny weedy little plants, still recognisable as

Spiralis by the twisted pattern of the small stem

and developing leaves and flowers. These are

probably first generation specimens germinating

straight from a seed underground that has been

nurtured by an associated mycorrhizal fungus.

We do not know how long Spiralis roots take to

mature, maybe longer than its bigger cousin?

The plant (RIGHT) was on the bigger side of

normal lone plants but not nearly as large as

some grouped specimens found further up the

dune.

Large groups of specimens can be well anchored

in hard dune slopes or bottoms and have

broadened their base by developing 3 or 4 (or

more) offshoots that bind them to the

compacting ground and enable them to produce

strong shoots and buds much bigger than those

of solitary plants..

Research Area…

This section of Strandhill on the LEFT is a very valuable area for all who like to recreate outdoors. It is between the Golf Course, the High Dunes, the Surfer’s Paradise and the long Atlantic Strand loved by people and their dogs. In between all of this lies a magical zone for those fascinated by Botany and Natural History. It is a treasure, perfectly safe and free from disturbance where everybody smiles — or is that at the sight of an elderly man throwing himself on the ground? It takes all sorts! The little javelin symbols (216) represent S. spiralis plants. (Click on Map for a larger view) The total number present are hard to guess but this central area is important as it has numerous stable sand dunes interspersed with mounds, sandbanks and numerous little paths. The clustering of specimens is due to selection; we have only surveyed parts of the dunes and many separate areas. Most of the central area will have Autumn Lady’s Tresses present. It is the ideal habitat for them, short grass, wet pools and drains, sandy and settled areas and no large plants to shelter them.

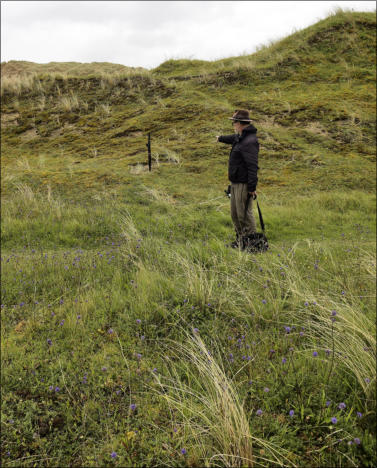

Typical example of the terrain. These empty herb covered flat valleys and gentle stabilised hills are uncrowded

and walkers rarely stray off the gently worn path to my right… No grazing or interference harms this place!

Ages of these Orchids:

All orchids can last for years but may not flower every year. They are innately perennials but are obviously

vulnerable at their early stages. A seed, and it is probably a local seed, settles in the sandy sward and may

become embedded. It then needs to form an association with an established mycorrhiza (fungal network)

from which it derives nutrients whilst developing an underground root to the stage where it can produce a

shoot and eventually another flower. These ‘new babies’ are tiny but numerous like grass seed; so many die

but some survive for the following Winter (or many Winters). Each year they are stronger, taller and with more

flowers, eventually producing sibling plants growing from buds off the original plant’s root.

PHOTOGRAPHY

The essence of modern botany is good quality photography. The day of collecting and pressing are (normally) gone or are the preserve of herbariums. To produce comparable quality digital images we use semi-professional SLR cameras. Smartphones are amazing but for fine detail, ability to explore an image, depth of focus and colour matching modern specialised cameras are essential. The lens shown ABOVE is a macro lens focussing from close-up to infinity. At a metre it will fill the screen and also have a valuable depth of focus, i.e. that part of the plant that we want to see clearly.The Habitats…

The ideal location will have low sward, be based on calcareous sand or grassland or settled dunes with diverse but typical flora associates, e.g. violets, Lady’s Bedstraw. Wild Thyme, but few if any large bushes or trees. Much of the Strandhill promontory shown in the Map above has very low vegetation. Other parts have waist high grasses and no orchids. S. spiralis will not grow in such areas. The image (BELOW) would show vegetation as high as the Orchid can be happy with.

A

B

C

D

Identifying Habitats.

The aspect and attributes of the land effects these Orchids considerably. They are quite tolerant and widely dispersed but will NOT grow in certain areas, e.g. overgrown land. We have classified habitats as a base for recording specimens, on an ABCD system as met on traversing the dunes from the main entrance off the backstrand. A: Wet Hollow. As the main path crosses the dunes and enters the flatter middle, a series of very low moist flat areas with often standing water and damp edges is found. Gentians and Frog Orchids abound in the wetter areas and the Autumn Lady’s Tresses are present on the small raised drier banks. This may be regarded as a nursery as many specimens seen here were delicate new plants in their first year of life above ground. B: Frog Orchid patch. Further in and to the left is a flat area with larger dry ponds and higher sandbanks in the middle and dunes to the side. Many medium sized Spiranthes spiralis occurred along the lower slopes of these humps but at varying height. We are not suggesting water deposition here as the water is evidently very temporary. C: Long Hillock. Some sand dunes are just round, this one had attitude that evidently appealed to some sectors of the Spiralis population. They could settle here. The area is situated to east of Zone B with most of the specimens being found on the west facing slopes of this sheltered lowland. D: Big Plants zone. This is a long well weathered valley leading northwards towards the high sand dunes. It looks older and more consolidated than areas to the south. Why this should be we don’t know. Perhaps, being close to the high sand cliffs these mature dunes pre-existed the large washout of the central part of the reserve? Image of the area (RIGHT) shows higher dunes with marram colonisation starting at the tops and the flat valley floor and slopes with short vegetation and a few sandy areas. The Spiralis here were found at the bottom of the slopes. (LEFT) Impact of stable ground on plants: Here are the plants marked on the Right. The secure stable habitat seems to have enabled these specimens of S. spiralis to settle down here. The presence of 3 or more stems arising close together suggests that these mature vigorous plants have been in the same place for several years; the plants have a common ancestor which may (or may not) be still there. The sturdy nature of these specimens supports a theory of long existence. These plants are growing from well resourced roots?Morphology and Detail:

The detail shown below brings up interesting queries about the Natural History of this species. On the LEFT elaborate features can be seen on the middle flowers. These are the the frilled borders that rapidly turn bright orange as both this species and S. romanzoffiana flowers mature. It seems like these ornaments may have some special function. Both species are fertilised by Bees and neither species has a spur (the nectar secreting pouch that rewards insects). Is this simply a landing zone or does the tubular flower, without a spur, feed the visiting bees?Perennial plants growing on stable ground!

Apparently Spiranthes spiralis is a very slow growing and long living orchid that takes about 10 years to develop underground before flowering. This growth is commensal depending on suitable mycorrhiza being present in the soil. But, with a very large population densely crowded together this fungus will naturally be in the soil. It may survive for another 10 years above ground but with seasons of flowering being a severe draw on the plant’s resources. It is also possible that plants growing together (like above) don’t automatically come from the same stock as this is a species that produces huge volumes of seed from large numbers of plants and much of that seed only spreads locally. (How on earth do they know that?)The Plants:

This is a charming plant with a very interesting history. In Strandhill and other places it thrives in conditions that suit it. Unlike S. romanzoffiana this is very much a terrestrial plant. It relies on wind to disperse its seeds and these then take many years to appear above ground. It is the same genus but different lifestyles. We present a variety of different specimens here, with their habitat, and close-up images of their morphology and lifestyle. Happily an un-complicated species with no hybrids!

Yellow Wort Blackstonia perfoliata

Odd dune plant, also of the

Gentian family, has stems that

perforate the centre of the

pointed leaves!

Occurrence and Natural History of

Autumn Lady’s Tresses

in Strandhill and The Mullet (Mayo)

We started this page (last year) as a general site reflecting the rich diversity of the

Strandhill Dunes and surrounding land and sea. It is a very rewarding area for Birds,

Insects and a large variety of Orchids — one which we now feature….

Many of the Spring/Summer orchids have been portrayed above but two species

persist well into the Autumn. The rest of this page shows some of our pictures of

Autumn Lady’s Tresses that are abundant in good years through many parts of the

Dunes where short grass and other vegetation allows them to seed and breed.

Two more images of the

Gentian to compare it with the

related Yellow Wort, opposite.

BELOW:

Little Emerald Moth

Jodis lactearia

An amazing tiny caterpillar

taking a lunch break to

relieve itself on a seed

capsule of a Marsh

Helleborine. The animal is

delicate, the picture is small,

but we have included a

larger image!

This is often found on trees

but spotted here near the

ground resting on a Marsh

Helleborine seed pod. A

widespread palaearctic

species. It favours trees and

chalk so maybe the shell

content of these dunes suit

it?

Rosettes and Late Flowers

These 4 images were taken on 18th September 2020. They focus on this plants great ability to reproduce vegetatively and in a surprisingly different format than their cousins, S. romanzoffiana. For comparison with that species refer to our now largely completed Spiranthes 2020 Survey. Having come to know romanzoffiana much earlier in our botanical career we were puzzled by writers who referred to that species having rosettes. It doesn’t! It has lateral buds emerging from the flowering stem just below ground level in Autumn. But, S. spiralis does have rosettes and very remarkable ones — as seen BELOW LEFT. These start with the growth of ‘a lateral bud’ on the underground stem but the end product is a cluster of 3 to 6 broad leaves emerging in September around single flowering spikes. Interestingly these spikes may still be in full or partial flower — as shown by images surrounding this section. The small plant (ABOVE RIGHT) must be struggling to produce both seed and rosettes so late in the year.

A magnificent clump. RIGHT

These 4 large specimens were first noted at the end of August

when there were no signs of rosettes. How quickly they emerge;

what triggers it? The present dense cluster of rosettes must

represent at least the 4 flowering plants and, possibly, other

non-flowering specimens underground. These plants could be

related or perhaps just close neighbours.

A single plant.

As Autumn commences the 1,000’s of Autumn Lady’s Tresses present

start to generate rosettes. At first these may not be visible but pull

back some of the moss and they can be seen to be rapidly developing.

These rosettes, made of several very broad and flattened leaves, are

the solar panels of this species and survive through the Winter helping

the development of their own enlarged root or tuber.

Keys to the sudden occurrence of

Spiranthes spiralis

in huge numbers and

seemingly spontaneously.

See UPDATE 2020 showing more Autumn plants and many

details of Autumn Lady’s Tresses, Spiranthes spiralis

Spiranthes spp. overwintering in Ireland:

RIGHT Subsequent research has unearthed this fine picture of an Autumn Lady’s Tresses rossette (12/2/2020). This was from an earlier walk on a cold winter’s morning in the same place as studied above. The rosette seems to have been affected by frost or a slight dusting of snow. But it was a strong and healthy specimen and, one assumes, contributing to the survival and health of this particular plant. No remnants of the former flowering stalk was seen but many more of these overwintering orchid rosettes were scattered all over the low mossy vegetation. The British Ecological Society has made a very detailed monograph of this species available on line HERE. This answers many of the questions we have been mulling over in regard to this species.. It is technical but quite readable and very interesting. For local information do feel free to Contact Us. Far RIGHT we show an image of the other Spiranthes’ vegetative survival device. These are the ‘lateral buds’ of S. romanzoffiana holding their own out of season. Interestingly they are much more modest and bode poorly for healthy survival of the species over Winter. But, they can survive underwater in Winter and have been observed under panes of ice along the L. Allen shore. The Thumbnail (RIGHT) links to a series of photos showing development of the romanzoffiana lateral buds off-season (July to April). This is a PDF so it may take some time to upload but all the many pictures can be examined in good detail. The story follows the life of Banksy, Rocky, Centra and Twins over the Winter of 2013/14 Rocky is on the right in front of the Euro and this image is from 22nd October 2013. The comparison with spiralis is striking with that orchid appearing to have a much more effective way of trapping energy and feeding its ‘root’ overwinter. But, of course, the lateral bud is the actual future leaves of next seasons plant, whereas the rosette only functions until a new shoot develops in July and and then disappears as a healthy new plant with (hopefully) a flower takes over.

Spiranthes spiralis rosette

12/2/2020

Spiranthes romanzoffiana lateral bud

22 / 10 / 2013